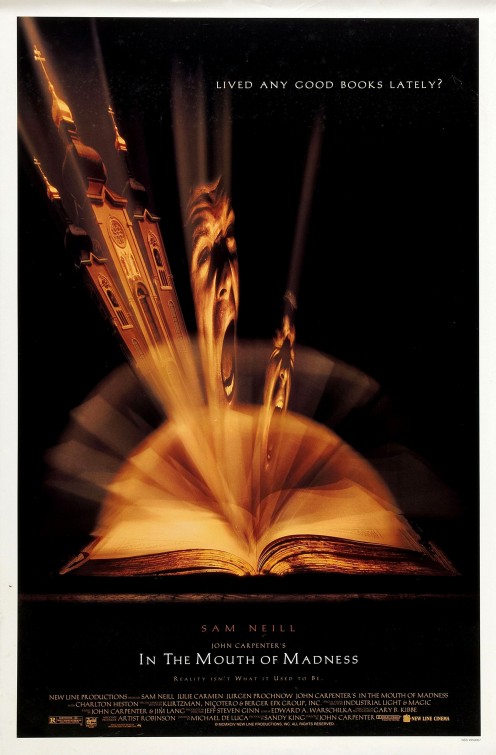

Whether all hell is breaking loose or imagination is manifesting itself, the notion of reality becoming fantasy is an intriguing one, a notion that Carpenter doesn’t fail to realize, nor does he stray from it. He simply runs with it as he gives life to a world in which being driven to the brink of madness is accentuated by Lovecraftian monsters, unsettling visions, mass hysteria, and losing grip on reality, all of which take their toll on John Trent and leave an impression on him that nothing could have prepared him for, which, in addition to the fact that he enters Hobb’s End with very little knowledge of it, gives it an aura of mystery, which illustrates that there is more going on than the disappearance of Sutter Cane.

There are quite a few details, such as a painting which is seemingly alive; red lines on the covers of Cane’s books which align and mark the location of Hobb’s End; and a stained glass window depicting a battle between a demon and an angel. Although these are brief, they are worth paying attention to because they convey that there is a subjectivity to reality and that the battle between good and evil is at its peak, an aspect that is well-conveyed given the effect that Cane’s books have on their readers and the fact that Trent is attempting to put an end to his agenda in spite of the fact that he only has so much influence. This is interesting in that it entertains the notion of free will as well as the distinction between reality and fiction; and as such, the idea that Trent is merely one of Cane’s characters is well-thought-out.

It’s worth noting that Carpenter’s depiction of the apocalypse isn’t limited to Hobb’s End; in fact, little is left to the imagination as the end of humanity is revealed through radio broadcasts and the pandemonium that erupts in New York. This illustrates how widespread Cane’s influence on his readers is, as well as the fact that they have lost their sense of self, what with taking pleasure in their savagery and transforming into eldritch abominations. Both are a simple but effective means of conveying that the end of humanity is at its peak and that the chances of survival are nil, demonstrating that Cane truly is evil, even going so far as to attain a godlike status of existence. This is the crown jewel of Carpenter’s depiction of the apocalypse.

In the Mouth of Madness has a lot more to it than I realized, and that’s what makes it so great. I’m sure that with subsequent viewings, I’ll pick up on more details, and even if I don’t fully understand it, it’s one of the few thinking man’s horror films, and for that alone, Carpenter and company have a winner on their hands.

No comments! Be the first commenter?